A zero-tolerance approach to talented jerks has its own dangers

One personality type occupies more attention in the workplace than any other. The “talented jerk”, whose alter-egos include such lovable characters as the “toxic rock star” and the “destructive hero”, is a staple of management literature. These are the people who smash both targets and team cohesion, who get stuff done and get away with behaving badly as a result.

So common and corrosive are these characters that plenty of companies spell out a zero-tolerance approach to them. “No jerks allowed,” says CARFAX, which provides data on vehicle histories. Netflix, a streaming giant, is similarly unequivocal: “On our dream team, there are no brilliant jerks.” The careers site of Baird, a financial-services firm, says that it operates a “no assholes” policy.

It is totally reasonable for firms to want to signal an aversion to genuine jerks. It may not actually put people off (“No assholes? Well, I guess Baird isn’t the company for me.”). But it sends an explicit message to prospective and existing employees, and reflects a real danger to company cultures. Toxic behaviour is contagious: incivility and unpleasantness can quickly become norms if they pass unchecked. That is bad for retention and for reputation. It’s also just bad in itself.

Moreover, the extreme version of the management dilemma posed by the talented jerk rarely exists in practice. The risk that you may be getting rid of the next Steve Jobs is infinitesimal. Just contemplate all the jerks you work with. If you really think they are going to revolutionise consumer technology, create the world’s most valuable company or have members of the public light candles for them when they die, you should probably just go ahead and make them the CEO. But the red-faced guy in sales who shouts at people when he loses an account is not that person.

That said, the enthusiasm for banning jerks ought to make people a little uneasy, for at least three reasons. The first is that the no-jerk rule involves a lot of subjectivity. Some types of behaviour are obviously and immediately beyond the pale. But the boundaries between seeking high standards and being unreasonable, or between being candid and being crushing, are not always clear-cut. Zero tolerance is dangerous. You may mean to create a supportive culture but end up in a corporate Salem, without the bonnets but with the accusations of jerkcraft.

The second is that jerks come in different flavours. Total jerks should just be got rid of. But they are rare, whereas bit-of-a-jerks are everywhere and can be redeemed. The oblivious jerk is one potentially fixable category. Some people do not realise they are upsetting others and may just need to be told as much.

Other people are situational jerks: they behave badly in some circumstances and not in others. If those circumstances are very broad (whenever the person in question is awake, say), then that tells you the problem cannot be fixed. But if jerkiness occurs only at specific moments, like interacting with another jerk, then it may be that a solution exists. If the thing that a talented jerk does really well can be done in comparative isolation or without giving them power over other people, consider it. As the well-known philosophical teaser goes: if a jerk throws a tantrum in their home office and no one is around to see it, are they really a jerk?

A third issue is one of consistency. This is not just about what happens when the person declaring war on jerks is also a jerk. It is also about the many other problem types who crowd the corridors of workplaces. Where are the policies that ban constructive wreckers, the people offering up so many ostensibly helpful criticisms that nothing ever actually gets done? Why not zap the brilliant fools who have blinding insights of absolutely no practical value?

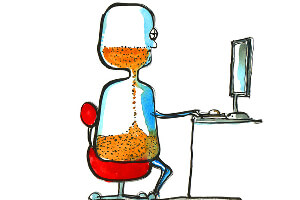

Above all, what about the pool of nice underperformers who putter along amiably and harmlessly, helping the culture much more than they do the bottom line? Talented jerks stand out, like shards of glass among bare feet: impossible to ignore, problems that have to be solved. Mediocrities are the bigger problem in many firms but are like carbon monoxide, silently poisoning an organisation.

Right-minded purists will argue that anything less than zero tolerance towards talented jerks is just pandering to people who behave badly. But right-minded purists will have skated over paragraph three and are a scourge in their own right. Someone ought to write a management book about them.